N-4: Storybook Love

Most of you asked for a neurospicy person's guide to surviving their 20s, but that is a lot to cover so it will take some time. Meanwhile, writing about why I named my guitar Beth. TW: SA.

2019: Context

After 1.5 years of going to therapy and still taking some terrible decisions, I suspected that what plagues me is more chronic than recent, I decided to get a diagnosis. It turned out that I have BPD and Complex PTSD, two chronic mental conditions, comprising of various symptoms like social anxiety, hypervigilance, extreme moods, perfectionism, a crippling sense of shame, intense rage, delusions, unstable sense of self, age regression etc.

2023: Part A

I spent the next two years in a vigorous attempt to improve myself. Cut out social media. Ate healthy. Worked out. Lost weight. Did well at work. Went to therapy regularly. Survived a pandemic. Built a home.

But every time I would be in a social setting around my parents, at work or in romantic involvements, my behaviour switched. all I could feel was unsafe. My only safety was in being alone. Once the pandemic ended, I changed my job and joined a very hectic workplace. It was a role that made all of my worst fears come to life- the biggest one being the feeling that I wasn’t good enough. I eventually quit and ended up in a situationship where I was trying to be the chill girl so he would fulfil my emotional needs (we all know how that ends, don’t make me write it). By the end of it all, shame had replaced my sense of self, and whatever I built of myself in 2 whole years had fallen apart. Every time I looked in the mirror I saw my brokenness- an illness that could never be cured. To think about it was to think about a sun drowning into a sunset and never rising up again. In a desperate attempt to ‘fix myself’, I found a DBT therapist, and opened my already overflowing can of worms in the first session itself. I told her that it takes one thing in my life to go wrong for everything to go wrong, and everytime something good happens, it is only a matter of time until my illness raises its head and I’m back into the shame spiral.

“Why do you think this is an illness?”

”Because it *is* a disorder, isn’t it?”

”Do you think it is fair to call someone’s entire personality a disorder?”

”No.”

”What if we were to think that yours was just another type of personality?”

”I-”

”Can you do me a favour? As homework, please write parts of your personality that you wish to change and the parts of yourself that you actually like.”

This is what I wrote:

Just writing this made me feel less flawed and more human. It felt like void in my brain was filled with light. With all my patches, I felt whole. Like the kids would say these days, radical acceptance entered the chat.

2023: Part B

In a fit of parental estrangement, my need for validation (and exploration) arose. I hooked up and got violated by two different men within a span of a month. By the time I could realise that things weren’t exactly consensual in the first encounter, another non-consensual encounter with another man I trusted had already happened.

There’s a different kind of shame you feel upon being violated once you’re older; the hate you feel for yourself is much, much greater, because you expect yourself to have gotten better at seeing it coming after all the years of working on yourself. There’s no excuse for the times you held them even after what they did, let them sleep on the same bed as yours, cooked for them, asked them to meet you again. All the work you did on yourself feels like a lie and you’re back to the only emotion you’ve felt all your life - shame; the biggest sense of which lies in telling people what you’ve been through, because all they can do is feel sorry for you. What the fuck does one even do with that?

Like I said, it takes only one thing to go wrong in my life for everything else to go wrong. I would either watch myself be functional (go to work, laugh with colleagues, juggle music school and guitar classes, binge-watch Gossip Girl, eat ordered food, buy a new guitar), or stare at the ceiling, revisiting each & every sequence of the two events and trying to change the way they happened. And no, it was rarely about the assault, it was about not kicking them out right away and treating them with the affection they didn’t deserve. How lonely was I to have done that to myself? This wasn’t the first time something like this happened, if I didn’t get better after all these years, could I ever stop this from happening again?

Part C: Beth

A saviour through this time had been doomscrolling, during which I happened to find my guitar teacher’s story of CSA. After my friends, she was the only person I trusted enough to tell what happened. Her advice was the closest thing a spoken word had come to feeling like a hand on my shoulder.

“Just keep playing your guitar and breathe with it. When the thoughts come, just continue picking the pattern and do not stop.”

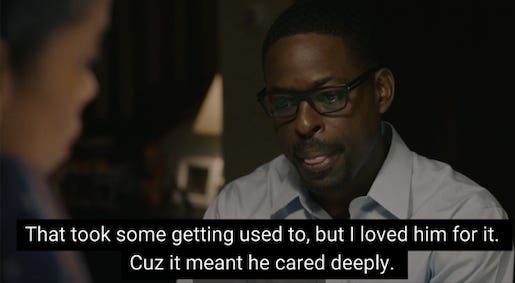

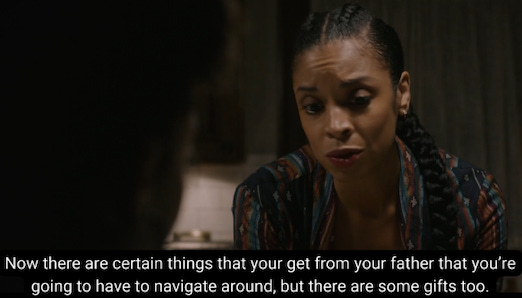

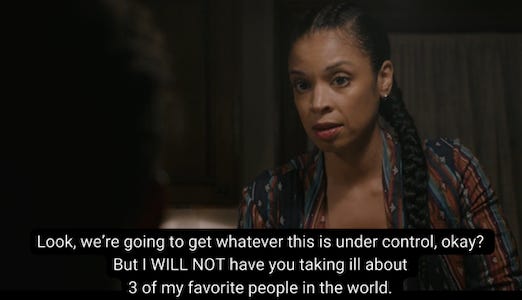

I wanted to cry but couldn’t. So I did what I do in my moments of emotional constipation- watched this plunger of a show called This Is Us (S04, E05). Coincidentally, it was exactly what I needed. Beth and Randall (he has genetic anxiety disorder)’s daughter has a panic attack and hates her dad for the genes. Beth calls them both downstairs and tells them this.

The plunging worked. The waterworks began.

The next day, I picked up my guitar and the shame struck again. I kept playing. Through all the flashbacks, my guitar was my only connection to reality. It made me remember who I was outside my shame - A kind, thoughtful and creative person with an impeccable sense of humour (I know barely 2 people who are funnier than me pls).

What most people don’t understand about neurodivergent people is that we are very often consumed by our virtual world - the regrets, the shame, the could haves the anger, the sense of betrayal, the delusions. It’s the only place where we have ever felt safe, so we end up painting a scene so vast that the canvas wraps us in it. While there’s no way to stop that from happening, our only hope is that there’s enough room on the top to let some air in, and that we’ll have people to remind us that there’s a world outside the canvas. Beth was Tess’s reminder that she was more than her illness. My guitar was mine. My connection to reality was the music that kept getting better every time I held on to it. It made me want to breathe more and get out of the canvas I was wrapped in.

I don’t think I would ever have to call my guitar by its name (it’s a bit corny in my opinion), but if I do, I hope you get why her name is what it is.

Fin.